September 26, 2013

The first scoop of soil analyzed by the analytical suite in the belly of NASA’s Curiosity rover reveals that fine materials on the surface of the planet contain several percent water by weight. The results were published today in Science as one article in a five-paper special section on the Curiosity mission. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Dean of Science Laurie Leshin is the study’s lead author.

“One of the most exciting results from this very first solid sample ingested by Curiosity is the high percentage of water in the soil,” said Leshin. “About 2 percent of the soil on the surface of Mars is made up of water, which is a great resource, and interesting scientifically.” The sample also released significant carbon dioxide, oxygen, and sulfur compounds when heated.

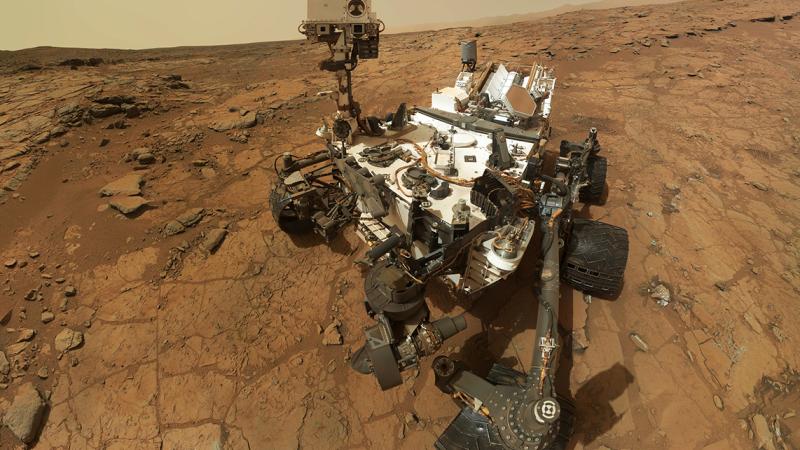

Curiosity landed in Gale Crater on the surface of Mars on August 6, 2012, charged with answering the question “Could Mars have once harbored life?” To do that, Curiosity is the first rover on Mars to carry equipment for gathering and processing samples of rock and soil. One of those instruments was employed in the current research: Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) includes a gas chromotograph, a mass spectrometer, and a tunable laser spectrometer enabling it to identify a wide range of chemical compounds and determine the ratios of different isotopes of key elements.

“This work not only demonstrates that SAM is working beautifully on Mars, but also shows how SAM fits into Curiosity’s powerful and comprehensive suite of scientific instruments,” said Paul Mahaffy, principal investigator for SAM at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. "By combining analyses of water and other volatiles from SAM with mineralogical, chemical, and geological data from Curiosity’s other instruments, we have the most comprehensive information ever obtained on martian surface fines. These data greatly advance our understanding of surface processes and the action of water on Mars.”

“This is the first solid sample that we’ve analyzed with the instruments on Curiosity. It’s the very first scoop of stuff that’s been fed into the analytical suite. Although this is only the beginning of the story, what we’ve learned is substantial,” said Leshin, who co-wrote the article, titled “Volatile, Isotope and Organic Analysis of Martian Fines with the Mars Curiosity Rover.” Thirty-four researchers, all members of the Mars Science Laboratory Science Team, contributed to the paper.

In this study, scientists used the rover’s scoop to collect dust, dirt, and finely grained soil from a sandy patch known as “Rocknest.” Researchers fed portions of the fifth scoop into SAM. Inside SAM, the “fines”—as the dust, dirt, and fine soil is known—were heated to 835 degrees Celsius.

Baking the sample also revealed a compound containing chlorine and oxygen, likely chlorate or perchlorate, previously known only from high-latitude locations on Mars. This finding at Curiosity’s equatorial site suggests more global distribution. The analysis also suggests the presence of carbonate materials, which form in the presence of water.

In addition to determining the amount of the major gases released, SAM also analyzed ratios of isotopes of hydrogen and carbon in the released water and carbon dioxide. Isotopes are variants of the same chemical element with different numbers of neutrons, and therefore different atomic weights. SAM found that the ratio of isotopes in the soil is similar to that found in the atmosphere analyzed earlier by Curiosity, indicating that the surface soil has interacted heavily with the atmosphere.

“The isotopic ratios, including hydrogen-to-deuterium ratios and carbon isotopes, tend to support the idea that as the dust is moving around the planet, it’s reacting with some of the gases from the atmosphere,” Leshin said.

SAM can also search for trace levels of organic compounds. Although several simple organic compounds were detected in the experiments at Rocknest, they aren’t clearly martian in origin. Instead, it is likely that they formed during the heating experiments, as the non-organic compounds in Rocknest samples reacted with terrestrial organics already present in the SAM instrument background.

“We find that organics are not likely preserved in surface soils, which are exposed to harsh radiation and oxidants,” said Leshin. “We didn’t necessarily expect to find organic molecules in the surface fines, and this supports Curiosity’s strategy of drilling into rocks to continue the search for organic compounds. Finding samples with a better chance of organic preservation is key.”

The results shed light on the composition of the planet’s surface, while offering direction for future research, said Leshin.

“Mars has kind of a global layer, a layer of surface soil that has been mixed and distributed by frequent dust storms. So a scoop of this stuff is basically a microscopic Mars rock collection,” said Leshin. “If you mix many grains of it together, you probably have an accurate picture of typical martian crust. By learning about it in any one place, you’re learning about the entire planet.”

These results have implications for future Mars explorers. “We now know there should be abundant, easily accessible water on Mars,” said Leshin. “When we send people, they could scoop up the soil anywhere on the surface, heat it just a bit, and obtain water.”

In addition to her work research as part of the Mars Science Laboratory Team, Leshin is Dean of the School of Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where she leads the scientific academic and research enterprise at the nation’s first technological university.