October 6, 2015

New research shows that a single conserved mechanism governs the movement of two structurally distinct variants of kinesin-14 – a class of molecular motors that moves materials and facilitates chromosomal separation within cells. The finding indicates that a mechanism using strain to advance the protein along its path has survived the pressures of evolution in diverse designs of motor proteins within this subfamily of kinesins.

Motor proteins are nanoscale machines that ferry cargo along microtubules, the molecular highway system throughout the cell. To the untrained eye, motor proteins resemble a stalk with arms that attach to cargo, and two legs with globular motor domains as feet that step along the microtubule. Each step requires energy that is harnessed through ATP hydrolysis to generate force. In most kinesin-14s, including kinesin-14 Ncd, a variant found in fruitflies, both motor heads can bind ATP. Yet, Kar3Vik1, a kinesin-14 found in budding yeast, is unique in that it has two motor heads but only the Kar3 motor head can bind ATP. The Vik1 motor head cannot because it lacks an ATP binding site.

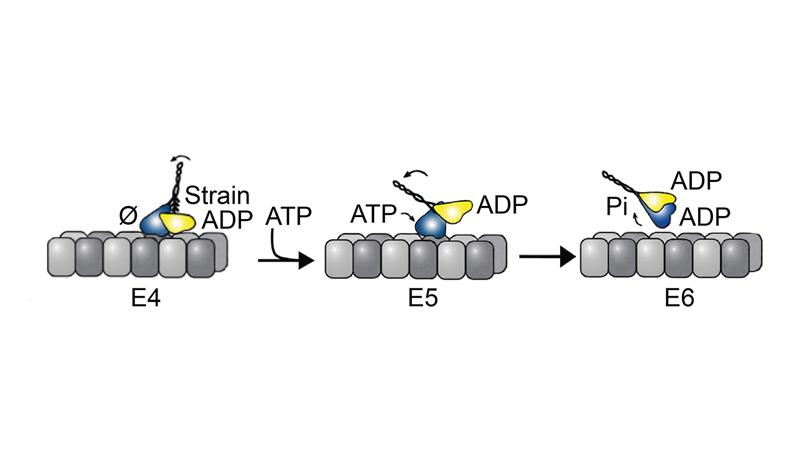

Kar3Vik1 is able to advance along the microtubule through a combination of ATP turnover on Kar3 and uses strain to pull the Vik1 head off of the microtubule through a rotation or powerstroke of the coiled-coil stalk.

“The question is: Is this strain-dependent mechanism unique for the yeast motors, or is it conserved evolutionarily? Can we come up with a mechanism (which we did) for homodimeric kinesin-14 Ncd – a motor protein with two equivalent heads, both binding and hydrolyzing ATP – that uses the very same mechanism as we see in the yeast motor?” said Susan Gilbert, professor of biological sciences at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), and co-author of the study.

The research, “Drosophila Ncd Reveals an Evolutionarily Conserved Powerstroke Mechanism for Homodimeric and Heterodimeric Kinesin-14s,” is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research combined experimental results (led by Gilbert) and computational modeling led by Juergen Hahn, professor of biomedical engineering, to validate the conserved powerstroke mechanism.

Under the mechanism the researchers developed, strain, which is so obviously critical to advancing the yeast protein, also plays a role in the fruitfly protein, popping the connection between the weaker bound motor head and the microtubule.

Gilbert said it would have been easy to dismiss the mechanism of the yeast kinesin-14 as one functioning only in lower order, single-cell eukaryotes, with higher order eukaryotes from Drosophila to humans using a completely different mechanism. Instead, the yeast motor Kar3Vik1 shed light on the true mechanism of kinesin-14 Ncd, and the evolutionary importance of strain.

Gilbert, head of the Department of Biological Sciences at Rensselaer, teamed with Juergen Hahn, professor and head of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, performed this research in the Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies, a unique environment that fosters multidisciplinary collaboration. Other authors also included Pengwei Zhang, a graduate student supervised by Gilbert in biological sciences, and Wei Dai, a graduate student supervised by Hahn in chemical engineering.