Numerous applications for special glass may include tougher smartphone screens and transparent structural materials

September 23, 2019

TROY, N.Y. — If you’ve ever dropped your smartphone on a concrete floor, you know that dreaded feeling as you turn it over to see how badly the screen has cracked — but that stress may soon be a thing of the past. Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have discovered a way to make glass less brittle and less likely to break.

Their findings, led by Yunfeng Shi, an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Rensselaer, were recently published in Nano Lett.

The glass currently used on many smartphones belongs to the oxide glass family, in which silicon atoms generally bond to four oxygen atoms. That type of bonding arrangement creates a rigid glass network that doesn’t allow plastic deformation. So, when significant external stress is applied — as it is when a phone is dropped on a hard floor — the glass breaks.

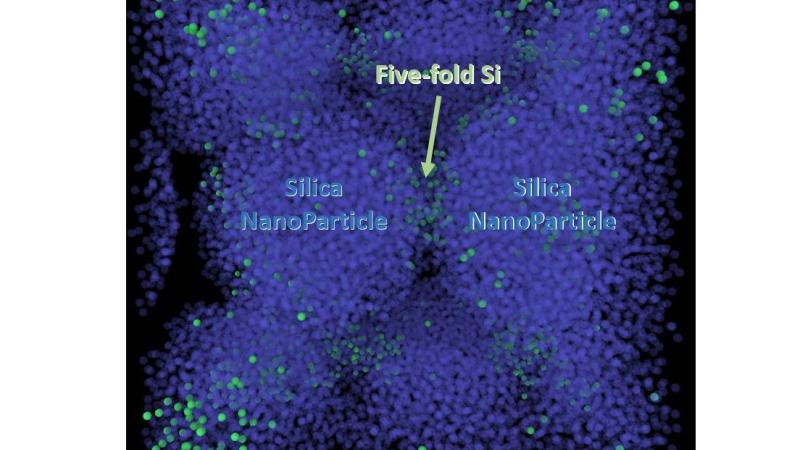

What Shi and his colleagues found through molecular simulations was that silica glass, made by compressing silica nanoparticles together, can be stretched up to 100 percent without breaking. They also discovered that the enhanced ductility emerges when silicon bonds with five oxygen atoms instead of four, Shi said. This is known as five-fold silicon, and it’s capable of shear flow under stress.

“The compression actually changes the material structure,” Shi said.

This enhanced plasticity enables the glass to withstand more load without fracturing. Beyond our phones, the potential of this finding extends to numerous applications.

“This glass is actually as stiff as steel. So, if the glass can be toughened sufficiently, it can replace steel,” Shi said. “Our holy grail is to make a transparent structural material.”

This discovery was made through molecular simulations. Now, Shi said, the next step is to test it in the lab.

Yanming Zhang, a graduate student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, is the first author on this paper. The work was done in collaboration with Liping Huang, a professor of materials science and engineering. It was supported by the National Science Foundation.