Volcanic winters wiped out all non-dinosaurian, non-insulated reptiles during the End Triassic Extinction, allowing large dinos to dominate

July 20, 2022

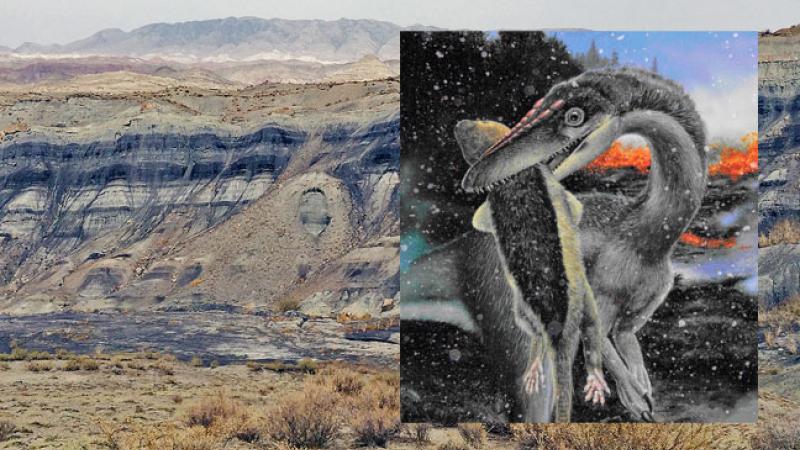

About 201 million years ago, volcanic eruptions covered an area roughly the size of South America in lava as Pangaea started to split. The Earth was changed. In the years that followed, 40% of all four-legged land animals were wiped out in the End Triassic Extinction (ETE). The exact cause was unknown.

However, researchers recently discovered that atmospheric changes as a result of the eruptions caused freezing temperatures at high latitudes. The land animals that survived had feathers or hair as insulation: large dinosaurs. Their survival over non-insulated animals, like prehistoric crocodiles, ushered in the large dinosaurs’ era of dominance.

Morgan Schaller, associate professor of earth and environmental sciences at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and a research team led by Paul Olsen, a geologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, recently published their findings in Science Advances

“Previously, we had no evidence of the freezing temperatures from this time period,” Schaller said. “The evidence comes from ancient lakes, currently in northern China, that had formed at high latitudes during the Triassic Period. There is a unique assemblage of minerals and grains in lake sediments that are indicative of having been rafted out into deep water by ice.”

There is no evidence of polar glacial ice sheets in the Late Triassic and earliest Jurassic Periods. Forests grew as far as the land extended, and Earth was in a “greenhouse” state because the massive volcanic eruptions during the extinction caused about a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, warming the climate.

“Today, our carbon dioxide level is 420 parts per million,” Schaller said. “Back then, it was anywhere from 1,000 to 4,000 parts per million.”

The research shows that despite the high carbon dioxide levels, the temperatures in the Arctic dipped below freezing. The volcanic eruptions, in what is referred to as the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP), led to short-lived but dramatic volcanic winters, amid an overall global warming. The volcanic winters lowered the temperature by as much as 18 degrees.

“The eruptions most likely put a bunch of sulfate aerosol in the upper atmosphere,” said Schaller. “This reflected solar radiation and acted as a driver for cold temperatures.”

The volcanic winters lasted for a matter of decades, which is very fast in geologic terms. Then, they were followed by the opposite extreme.

“There were creatures living in the tropics that were adapted to warm temperatures and, suddenly, volcanic winters caused it to become very cold,” said Schaller. “Then, the sulfate collected on rain droplets and formed acid rain. The amount of reflected solar radiation decreased and temperatures went way up. It got cold really fast and then, gradually, became much hotter than it was before the eruptions.”

All in all, the findings point to the discovery of a rarely observed mechanism of extinction. Only creatures that could handle extreme temperatures survived the ETE.

“This insightful analysis carried out by Morgan Schaller and his team shows that if complex animals (such as dinosaurs) had already evolved resilient features that gave them enough time to further adapt as conditions were changing, they could survive extreme climatic and environmental upheavals,” said Curt Breneman, Dean of the Rensselaer School of Science. “These results will not only affect future studies in paleontology but may also inform us about the future of our planet.”

Paul Olsen and Morgan Schaller were joined in their research by Jingeng Sha and Yanan Fang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences; Clara Chang, Sean Kinney, and Dennis Kent of Columbia University; Jessica H. Whiteside of the University of Southampton; Hans-Dieter Sues of the Smithsonian Institution; and Vivi Vajda of the Swedish Museum of Natural History.