Grant will enable team to determine origin of ancient carbon pool in deep ocean

September 1, 2022

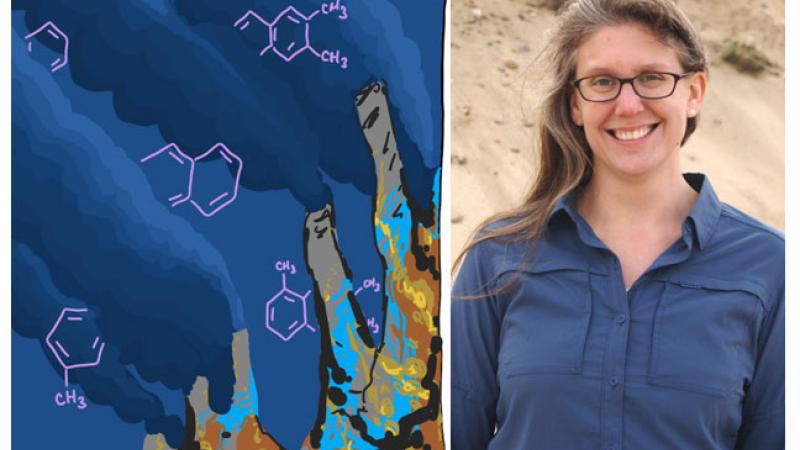

A few years ago, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Sasha Wagner, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences, proved false what scientists had thought for years. Soot-like molecules that formed an ancient carbon pool deep in the Pacific Ocean did not, in fact, originate from wildfires on land.

“We discovered that there was an isotopic mismatch,” Wagner said. “The isotopic composition of this refractory aromatic carbon is different on land verses what we see in the ocean.”

Around the same time, researchers from University of Delaware discovered bits of graphite at hydrothermal vents in the Pacific called the East Pacific Rise 9°N vent field. Graphite is a type of organic carbon and comprises part of the carbon pool Wagner analyzed.

Radiocarbon dating of the deep ocean carbon pool largely put it at 5,000 to 6,000 years old, with a fraction of this carbon pool at 23,000 years old. This also pointed to the carbon having a deep sea rather than terrestrial source.

It led them all to wonder, are hydrothermal vents the source of ancient aromatic dissolved organic carbon? They decided to join forces to find out.

Wagner will use a $467,853 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to analyze samples from the East Pacific Rise 9°N vent field near the western coast of Central America. Her research is part of a collaborative project led by University of Delaware’s Andrew Wozniak, George Luther, and Sunita Shah Walter (total NSF award for the project is $1,503,114).

Wagner will travel in the human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin submersible, best known for its use exploring the Titanic, to depths of about 3,000 meters to directly sample vent fluids, ocean water, and marine sediments. She and her team will use a suite of geochemical techniques to determine if their hypothesis is correct.

“The HOV Alvin was recently rebuilt and can now submerge to 9,000 meters and access 99% of the ocean floor,” Wagner said. “We will not use its full capability for this project, but it will be an amazing experience!”

Wagner will bring at least one Rensselaer graduate student with her on the excursion and, perhaps, an undergraduate, as well. As she makes plans, Wagner can’t help but recall her own undergraduate experience.

“I graduated from University of Delaware and took Luther’s environmental chemistry class as an undergraduate student,” Wagner said. “This is the ultimate full-circle experience. I remember Luther talking about going down in the Alvin submersible, and here I am, collaborating with him to learn new things about hydrothermal vents years later!”

The ocean’s dissolved organic carbon pool matches the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and is critical in maintaining the Earth’s carbon balance.

“By recognizing the subtle clue that isotope ratios of deep-ocean aromatic carbon compounds differ significantly from those on the surface, Professor Wagner and her team are on the verge of a major discovery in understanding the evolution of pre-historic Earth,” said Dr. Curt Breneman, Dean of the Rensselaer School of Science. “This high level of innovative thinking and thirst for experimental discovery is representative of Rensselaer faculty and students.”