October 24, 2017

[Four years ago, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai entered a relationship to promote personalized medicine and medical care through collaborations in education, research, and development of new diagnostic tools and treatments. Several innovative projects on Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, diabetes, and osteoporosis have already emerged from this partnership. As part of the relationship, the Icahn School hosted a Heath Hackathon, supported in part by the Rensselaer Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies, to explore transformative ideas in several areas of health-care delivery. The event, held October 13-15 in New York City, included Rensselaer students from all five schools, as well as students from Mount Sinai Medical Center, Columbia University, and CUNY, and hospital staff. Rensselaer students were part of all the three finalist teams who will compete for a Shark Tank-type showcase in February. In this post, the Approach spoke with Angela Su, a member of one of the finalist teams.]

As a doctoral candidate in computer science, Angela Su had been in hackathons before. But she’d never been to a health-care hackathon. So when she saw the notice about an event hosted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, she signed up. Forty-eight hours after she walked in, she and a group of people she had never met had designed and pitched a new app for pediatric cancer patients. And that’s just the beginning.

Su was one of a dozen undergraduate and graduate students from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who entered the Mount Sinai Health Hackathon. Her team, which also included Rensselaer biomedical engineering student Alagu Chidambaram, is one of three finalists. Finalists were awarded $2,500, and will participate in an innovation “Shark Tank-type” showcase on February 15, 2018, during which the finalists and a fourth wild card team will present a five-minute pitch to a panel of entrepreneurs.

Two Rensselaer students were on each of the two remaining finalist teams. Lydia Krauss, a biomedical engineering undergraduate, is working on “Helping Stand,” a portable device to assist fatigued patients stand to get out of a car. And Michael Bramson, a graduate student in biomedical engineering, is working on “StreamLine,” an AI-based tool for streamlining the clinical trial protocol development process.

The multidisciplinary competition focused on creating novel technology solutions for assessing, monitoring, managing, and treating problems in health care, with a focus on cancer. Entrants were first given an overview of problems in cancer prevention, diagnosis, management, treatment, and recovery. Then entrants generated solution ideas, such medical devices and apps, and teams coalesced around the ideas. Teams designed and refined their solution during the event, and presented them before a panel of judges.

The format made it possible for teams with a diverse skillset to work together, said Su.

The hackathon started with problem statements, basically an overview of problems that hospital and patients face in cancer treatment. I don’t have a medical background, and I don’t know the leading-edge problems in cancer and cancer research, so hearing the problems made it easier for me to bring my skills to bear in a new field.

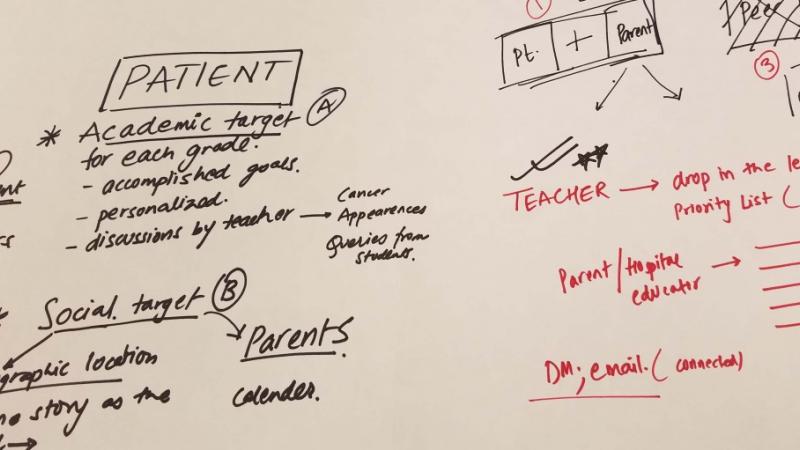

Su and her six-member team designed “On track,” a web-based school and socializing tool for pediatric cancer patients. The tool makes it possible for parents and teachers to keep kids connected with their classroom and peers as they undergo treatment.

Su said her team took a systematic approach to developing their solution.

My team ended up being super diverse, everyone came from different backgrounds – biomedical, education, computer science. Everyone had a different role, and we worked really well together. We did a lot of background research to see what kinds of problems pediatric students might be going through, what resources are available, and how our potential solution would be helpful. During the event, they had mentors circulating among the teams – clinicians, business people – and they gave us great advice on how to shape our idea.

The team intends to develop their idea. In the brief time since the hackathon, the team has already reached out to potential industry and academic partners including Rensselaer’s Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies and Institute of Data Exploration and Application, and is discussing how they can take their idea from design to reality, Su said.

There’s a lot of potential. It’s crazy seeing it go from a problem and idea to a product. What’s we’ve designed thus far is a prototype, and we want to work on refining it and keeping that momentum going. If we’re able to do it, it would be great to partner with hospitals to use this app, so it could impact the children who need it.

Regardless of the outcome, Su says the event was a win.

This is an experience that I can carry into my career. For one thing, working on a team going toward a common goal is what I imagine it will be like in the workplace. Also, having autonomy to be in charge to work on this. Even the technical skills like learning about different technologies that are out there. We used IBM Watson software to automate some of the process and learned how to implement that. And it was a networking opportunity, meeting people in the hospital, in business, and other students. All of that is relevant to career goals.

Rensselaer students Joseph Osei-Kusi, Obeng Buo, Snehansh Pabba, Wan Na Chun, Gabrielle (Alex) Ford, Carissa DelGaudio, Kathryn Hollowood, and Smriti Moorjani also participated in the event.